In this part we begin by examining ideas and criteria to be met in group decisions and show that the AHP/ANP provides the best means to meet these criteria. We then go on to show how decision problems are structured as hierarchies, discuss some of the major technical aspects of the AHP and how to combine individual judgments into a representative group judgments and how to apply the ideas with group participation and illustrate them many examples. This is then followed by a chapter about yes-no voting versus voting according to intensity of preference. The role of the AHP in forward-backward planning is examined and illustrated and finally a chapter is dedicated to presenting the ANP. Complex decisions involve four kinds of merits with their own separate structures: Benefits (B), opportunities (O), costs (C) and risks (R) to which we often refer collectively as BOCR. Later we show how to obtain a single overall outcome by rating the top ranked alternative for each of these merits with respect to strategic criteria to derive weights for the BOCR and use them to weight and synthesize the final priorities of the alternatives that are derived separately in the substructures.

Of all participative management tasks, ensuring reliable and efficient group decision making may be the most difficult. There are several theories and techniques to support individuals and groups in making decisions. We show in this chapter that the AHP is the only group decision support process that does it in an integrated way. We develop criteria from the requirements for successful group decision making and show that the AHP meets each of them all in a remarkable way. We go through the challenges faced by group leaders and indicate the technique of the AHP that can be used to deal with them. The outcome of the group process is a set of priorities for the alternatives. These priorities can be used to choose a best one or to distribute resources proportionately to fund the alternatives when they are projects to be implemented.

The twenty years of Dennis Romig’s research on teamwork suggests that using a systematic and structured approach and having a clear definition of the problem are necessary but not sufficient to ensure success [1]. An organization can have more effective meetings by promoting team communication and using a method to manage the conflicts that may arise in the process. The more open the communication, the less likely a conflict will cause a breakdown. It has also been shown that a team’s creativity often leads to breakthrough ideas when team roles and responsibilities are clarified. There may be nothing new about this, but Romig’s results are significant because they validate the work of many experts who have been trying to find ways to improve group decision making.

People in organizations spend an enormous amount of time in meetings [2]. Some researchers have estimated in the late 1990s that:

Having an effective process to record the objectives, criteria, and alternatives and structure the decision is one sure way to prevent wasting time – our scarcest resource. This is why a systematic approach to decision making is so essential. The method we use here, the AHP, is a solid and rigorously validated approach [3, 4]. By using the AHP and its supporting software, a

group leader has a record of the group’s results as the discussion progresses, and when the process is finished there is a tangible outcome – a best alternative or a best allocation of resources. The model captures both the problem and the logical step-by-step history of the information given by the group. The model’s level of detail is at the user’s discretion. The leader can obtain feedback from the system that may prompt him to go back and review previous judgments – or even change the structure if necessary. One of the most important revisions is to add key elements that may have been missed. The group might not even realize that something is missing until the support system produces an outcome that differs from their expectations. People can make the division by relying on either rational thinking or intuitive thinking alone. The following examples illustrate this.

Ideas that appear reasonable in mathematics can lead to surprising paradoxes that may be logically valid but fail to match the reality we experience. Two of the twentieth century’s foremost mathematicians, Stefan Banach and Alfred Tarski, proved “a most ingenious theorem” that seems to be a paradox derived from well-known assumptions in mathematics. It is possible they proved, to dissect a solid sphere into a finite number of pieces and then rearrange these pieces so that each forms a ball exactly the same size as the original ball [5]. The only thing done to the pieces is that they are moved around in space like the pieces of a jigsaw puzzle. Their idea can be extended to three or four or any number of balls or a single ball can be formed that is twice as big as the original ball – or as one author put it, you can transform a ball the size of a pea into a ball the size of the sun. Thus logic can lead to ridiculous results that are unobtainable in reality. The outcome of logical thinking is conditioned by the assumptions we make, and these assumptions are often hidden and also very subtle.

Here is another example of the shortcomings of intuition. Imagine you are given a cup of coffee and a cup of milk with equal amounts of liquid in the two cups. A spoonful of milk is transferred from the milk cup to the coffee cup, the mixture in the coffee cup is stirred, and then a spoonful of this mixture is returned to the milk cup so that at the end the amount of liquid in the two cups is still the same. Is there more milk in the coffee cup or more coffee in the milk cup or what? Most people say there is more milk in the coffee cup; a few say the reverse; and fewer still say they are equal. Intuition tells us that the first transfer of milk to the coffee cup so dilutes the milk in the coffee that the best transfer of the mixture cannot take back much of it, hence leaving more milk in the coffee cup than coffee in the milk cup. Of course, not being able to take back much of it should make it possible to take a lot more coffee in the spoonful. But people do not think of it that way. Notice that whatever amount of milk is missing from the milk cup is replaced by an equal amount of coffee (and vice versa), because at the end each cup has the same amount of liquid with which it started. It is therefore obvious that there are equal amounts of coffee in the milk and milk in the coffee. We can verify this with an example. Suppose that we have 5 teaspoons of milk in the milk cup M and 5 teaspoons of coffee in the coffee cup C. One teaspoon of milk from M is transferred to C. After having stirred cup C adequately, one teaspoonful from C is transferred back to M. Cup C, after the first transfer, has 1/6 milk and 5/6 coffee. The teaspoonful transferred to M also contains the proportion 1/6 milk and 5/6 coffee. Therefore, the composition of the two cups will be as follows: M has 4 1/6 milk and 5/6 coffee; and C has 5/6 milk and 4 1/6 coffee. Thus, there is as much milk in the coffee cup as there is coffee in the milk cup.

We need to use both logic and intuition to deal with the world and the AHP helps us do this. The AHP/ANP processes have been rigorously designed and validated so that its users can be assured that with valid inputs the system will produce valid outcomes. If the result produced by the system differs from expectation, however, which is generally based on intuition, it does not necessarily mean that the intuition is wrong or the logical synthesis is wrong. The group needs to review the model to look for causes of deviation. They might find that the model itself needs revision or that their intuition is biased and needs to be changed. Perhaps the difference was caused by the alternatives simply being too close to be sensitive to small changes in judgment or maybe the group failed to recognize an important factor. When a group of executives in an engineering company used the AHP to make a decision about whether or not to go on with a troubled project, they did not feel the outcome of the AHP was correct and found that they had misplaced technology in their model. After some study, the group restructured the model and put technology at a higher level in the hierarchy so that it received more importance. They learned from the model that they had failed to appreciate the influence of technology.

When a group of MBA students tried to model a decision problem faced by the local government, their result differed from the decision announced by the decision makers (with whom they intuitively agreed). The students found that they had considered the benefits, costs, and risks of the project but not the opportunities. When they added opportunities and recalculated their results, they got what they expected. The Analytic Hierarchy Process is not free from the garbage in/garbage out phenomenon.

The AHP does not require a group to reach full consensus at every step along the way, but the group does need to show a certain level of coherence in their thinking to reach a credible outcome. They can ensure this by closely monitoring incremental results from the model as they proceed: Are the pairwise-comparisons sufficiently consistent? Do the priorities that result from a set of pairwise-comparisons look reasonable? The time to revise is part of the process as it moves along. The leader can also use the system to measure how much one person’s judgments differ from those of the group as a whole. A wide gap may indicate a diversity in knowledge that the group may be able to make use of; that one person may have new information the group was not aware of. Now is the time to present it, then-revote. If the differences are not great, the group can proceed to the next set of judgments. Now let us see how a systematic and structured approach contributes to success.

To make a good decision, we need to understand the problem. A model is a concise way to describe a complex idea; therefore it is a most effective tool for a group because it offers them a quick way to grasp the situation. Not only does structuring a model together help them to gain a collective understanding of the problem, but it can also be the means by which a diverse group of people with different backgrounds and aspirations can pass information back and forth and develop a consensus. One way to deal with disagreements is to use creativity techniques such as allowing group members to play roles. More and more people in organizations find themselves working in different groups doing project-based assignments. Because of the interdependency in objectives and tasks of today’s cross-project teams, there needs to be intergroup coordination. We need to advance from group collaboration to intergroup collaboration [6]. The AHP helps with this by specifying and prioritizing organizational objectives that are common to every team.

Identifying problems as they appear – and taking action to solve them – is a major decision-making activity. Failures may happen for several reasons. Why is it that we often do not anticipate a problem to prevent it from happening? When a problem arises, why do we still fail to perceive it? Similarly, why do we fail to see opportunities before other people do? Why do we fail to see threats? Even when we see the opportunity, why do we repeatedly fail to benefit from it? And when we finally do something to solve a problem or seize an opportunity, why do we often fail to succeed?

How can we become more sensitive to the signs of problems or opportunities? First, we need a way to help us see by providing contrast that forces us to pay attention [7]. Scenario planning is a way to direct our attention to scenarios that might be emerging from our current situation. There are two kinds of scenario planning. In the first kind, a composite scenario emerges as a result of different objectives of the various parties operating in the same environment. The AHP’s forward and backward planning has been applied to this kind of scenario planning [8]. The second kind involves predicting a drastic shift in the environment should a certain event occur. This is the process of considering a set of possible changes in the environment with the purpose of promoting understanding of each scenario. The objective is to be prepared with strategic decisions for each scenario [9]. Once the future scenarios are identified and understood, the AHP can be used for articulating the collective understanding and then producing strategic decisions for each of them.

Although we now can see problems and opportunities and realize that we need to change our strategy, we may still be reluctant to make the shift. We refuse to do new things because we do not know exactly how we should change our current best practices. And even if we do know, we are worried that we might do them poorly and wonder how they will affect our performance. We need to know how the new strategy translates into much clearer objectives – and, more importantly, what new actions are needed. Balanced Scorecards offer a systematic way to identify strategic objectives and actions along with their respective lag and lead performance indicators [10, 11]. But there are still two important issues that must be addressed. The first is ensuring the validity of the cause-effect relationships between objectives and actions. Even when this issue is properly addressed, the process tends to produce a lot of seemingly independent initiatives that may lead to uncoordinated actions within the organization. The second issue involves prioritization. Cause-effect relations have different intensities; not all initiatives have the same influence on the achievement of objectives; moreover, not all objectives have the same impact. Thus the second issue becomes a question of prioritizing the actions for the most effective way of implementing our strategy and then allocating resources accordingly.

In his books, Hubert Rampersad [12, 13] stretches the need for alignment even further by formulating frameworks for integrating Balanced Scorecards with several other management ideas in organizational change and learning. He introduces the Personal Balanced Scorecard, which promotes the alignment of an organization’s scorecards with its members’ personal scorecards. Striving for alignment requires a series of decisions. The challenge in implementing the AHP lies mostly in determining the objective of each decision and getting a group of people to work together to construct the hierarchy or network and provide the judgments.

The AHP/ANP is a great help in strategic decision making [14] and problem solving because it establishes a performance measurement record to track our progress and let us know how well we are doing. An excellent example of using the AHP for resource allocation is how IBM Rochester in Minnesota used it in the development of its successful new computer AS400 [15]. In IBM’s example, groups from different levels of management worked one after another using an elaborate framework of AHP to prioritize their processes. IBM Rochester also used the AHP to map its performance relative to its competitors with respect to the key factors for success in computer- integrated manufacturing [16]. IBM Rochester attributed in part its winning the prestigious Malcolm Baldrige Award to its use of the AHP.

Now we know where to go and what to do. Using our new map, we are ready for our journey. We may need to establish new standards and will surely need to improve the way we do problem solving, but now with the new objectives and perspectives in mind.

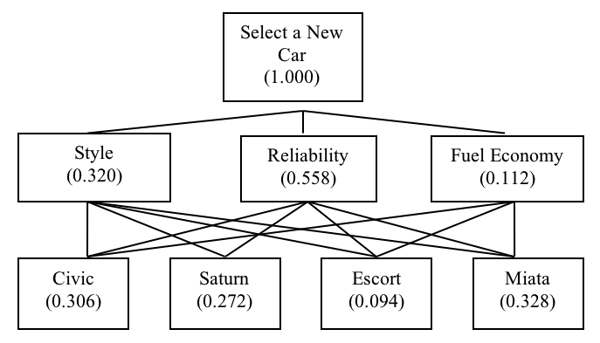

An example of a model is shown in Figure 3.1. A model can be considered as a special language for communicating complex and abstract ideas. This diagram tells a story about a person’s decision to buy a new car. The selection will be based on three criteria – style, reliability, and fuel economy – with four alternatives to choose from: Civic, Saturn, Escort, and Miata. The boxes and arrows show the structure of the problem; the numbers are the derived or synthesized priorities from a number of judgments systematically elicited. The priorities of the criteria indicate their relative importance, and the priorities for the alternatives are the final preferences for the cars. Having a model as a language is particularly useful if the problem is complex. In a decision problem, obtaining numbers that represent relative priority is particularly important. For a decision model to be valid, all the key decision elements must have been considered and the numbers must accurately represent the underlying order in the decision maker’s mind.

The same models used for individual problem solving and decision making can be used for groups as well. Involving people who will be in charge of implementing the decision in the decision-making process will enhance the likelihood of success because of the tacit knowledge they obtain from the process and because they are more likely to be committed to implementing a decision they contributed to shaping. Not only does an effective group decision create a sense of ownership, but having a structure is a way to align the participants’ understanding of a complex decision and its underlying assumptions leading to more coordinated collective actions after the decision is made.

Figure 3.1 A Model as a Special Language

Group decision making is about process. Since disagreement is inevitable, it is essentially a process to come up with alternative ideas and then to work on reaching agreement on the best policy or action. The group may disagree on what values should drive the decision process, on the consequences of a certain policy or action, or on the best policy or action among the set of alternatives being evaluated. The three types of differences are interdependent – a group cannot really resolve one type effectively without addressing the other two differences in an integrated way.

There are two ways to deal with group disagreement: the consensualist approach and the pluralist approach. Consensualists always work for consensus and do whatever it takes to avoid disagreement. A well-known modern philosopher of science, Nicholas Rescher, is a proponent of the pluralist approach. Rescher argues that working toward consensus is not about doing whatever it takes to reach agreement [17]. He maintains that pluralists: “Accept the inevitability of dissensus in a complex and imperfect world. Strive to make the world safe for disagreement. Work to realize processes and procedures that make dissensus tolerable if not actually productive.” Pluralists do work toward consensus, because decision making is about agreement, but they do not avoid disagreement or conflict. Consensus is not the same as unanimity.

Rather than being forced to accept plurality as a necessary evil we should seek out diversity in a group because this is the way to capture the complexity that will make our collective decision both relevant and useful. A group whose members have diverse knowledge, experience, values, and preferences has a better chance of arriving at a decision that is acceptable to all. Surely such a decision will have a better chance of being supported in its implementation. The more diverse the group, however, the harder it is to come to a decision in a democratic way because people will inevitably react differently to the same circumstances. The group’s leader must feel confident, therefore, that he will be able to manage this diversity to produce a useful outcome.

As Rescher has suggested, resolving disputes in group decision making means identifying exactly what has been agreed upon and disagreed about. Working in a group assigned a specific task does not mean that all members start with the same perception regarding the objective of the decision or know exactly what outcome is expected from them. A group needs to begin by setting a goal. The goal must be relevant to the problem at hand and formulated in such a way that makes clear what kinds of options are to be evaluated. In other words, we have to be sure that implementing the group’s decision will solve the problem. Having set its goal, the group then must collaborate to list the set of feasible alternatives and evaluate them to find the best one.

Generating alternatives is not always an integrated part of the group decision-making process; sometimes they are given with the task. But if the group has to generate the alternatives say for a new product, they may call on people with a additional kinds of expertise to do special research. Or, given a set of alternative courses of action, a group may have to choose the factors to consider and they may value the relative importance of the alternatives differently on these factors. Disputes may arise because they have different values or believe there are consequences that must be considered. Ultimately these differences may cause them to differ on what alternative is the best.

The AHP/ANP supports the plural decision makers in their quest to overcome their differences and converge to a solution. It is the means to address differences in values, consequences, and preferences in an integrated and systematic way within the context of the problem. Differences in values are addressed by determining what objectives are important; differences in consequences by determining the costs or risks involved in a decision; and differences in preferences by evaluating the alternatives with respect to each criterion. With this process the final preference is not discussed directly, and this should reduce the chances of a dispute regarding the final overall decision. Since it will be the logical outcome of what has been agreed to during the process, disagreement on the outcome would be settled by reviewing the process to find out why their expectations differed.

Organizations that experience confusion and conflict in decision making often attribute their problems to poor communication. They then try to overcome their problems by conducting employee training programs in communication or by investing in internal communication systems. Often, despite all the training and investment, the problems remain.

Collaboration aims at producing a tangible outcome; communication aims at the accurate transmission of tacit information from a sender to a recipient. The former is what we need for group decision making. Would better communication ensure better collaboration? We cannot be sure. Collaboration surely needs communication, but better communication does not always improve collaboration. In fact it may sharpen conflict because a side effect of improving communication is to make differences clear. Building collaboration is the goal for teamwork, rather than merely improving communication because it aims at collectively producing tangible outcomes [18]. A group of artists may collaborate to craft a statue for example, and a management team may work together to produce a model that describes its competitive environment and can be used to find the best strategy.

In a pluralist world that values diversity, collaboration in decision making happens when two or more people with complementary knowledge and experience working together create something neither of them could have done alone. They work together to focus their attention on the same problem even though they may perceive it differently. Despite their differences, they can think together as a unit, contributing their individual strengths to construct a model that represents their collective understanding of the problem. A decision aid should help people to both expand and sharpen their understanding. It does not necessarily mean that it must reproduce their hunches for answers. It should, however, make it possible for them to see what sort of judgments they need to espouse in order for their hunches to come about. This way they can deal with their differences as they arise, but they need only focus on those that are relevant and would affect the outcome. They would resolve conflicts regarding the model and ignore any trivial disagreements – a different process from compromise. There are differences that can be incorporated, differences that need to be discussed to build consensus, and differences that must be dealt with by allowing team members to express their views according to their expertise, authority, and perhaps power.

Mental models are sets of beliefs that involve certain assumptions about the world. They shape our perceptions and may lead us to see the world in a biased way. Our mental models not only play an important role in how we interact with the world but also contribute to forming our expectations [19]. Our brains interpret the reality we sense, filling the gaps by making assumptions based on our accumulated experience. Our minds are influenced too by our own genetics. Finally we base our responses on stimuli selected according to our own assumed reality. All these influences make people unique: we all see the same problem in our own way and hence react differently. As much as our differences may become the source of conflicts, they are also the source of the diverse knowledge we need in order to make better decisions.

Learning can be viewed as a conscious process of making mental models explicit so they can be developed and refined to respond to the world [20]. Interaction with other people helps. Although mental models are tacit, they drive behavior that is observable by other people. Group members can help each other to make their mental models more visible so that they can be questioned in order to validate the underlying assumptions of certain opinions or actions – especially when they deal with differences. As our mental models are developed and refined, they become aligned in the context of the problem at hand. Aligning the mental models can establish common descriptions to a useful commonly created description of the problem, opportunities, or systems that are of collective concern. Obviously this alignment calls for a group culture that values differences and does not attempt to squelch them. All this takes time and commitment to carry out.

>Collaboration involves a medium that the team members share to combine their contributions and produce a tangible outcome. This medium may be as simple as a piece of paper (where people draw together), a whiteboard (where people analyze a problem together), or a theater (where actors perform their roles in a play). The use of a common medium makes the process more productive because it depends less on perfect communication. The product of their collective effort practically speaks for itself. People can represent their ideas in the form of explicit and direct contributions that often convey their meaning and relevance better than words. With the AHP, the medium is a decision model on a computer.

A group involved in a collective decision-making task first needs to create a structure to represent their common understanding of the problem. Participants contribute their ideas systematically by proposing the elements of the problem such as criteria and the alternative courses of action. Setting a goal at the beginning and agreeing on the specific outcome they need to produce makes this process easier. They could start, for example, by using one of the brainstorming techniques to generate the set of alternatives they will evaluate [21]. They may write their suggestions on cards or post-it notes, to make them easy to organize, and then work together at the beginning to structure the elements on a whiteboard or flip chart [22]. The group facilitator can lead the process by asking specific questions to group elements that belong to the same cluster in the structure.

Up to this stage, there is no opportunity for conflict because it is not necessary to discard any ideas. When it comes to eliciting judgments on priorities, some agreement should be possible. If not, the group should go back and expand the model. The structure will help them make a series of specific judgments and will minimize unnecessary conflict due to misunderstanding (though there may, of course, be legitimate differences of opinion on specific judgments). When such disagreement occurs, the first step is to make sure the parties have the same understanding of the elements to be compared. The opposing parties can then present their reasoning. If this does not resolve the dispute, find out which party’s judgment is more consistent with the rest of the judgments using the AHP consistency check. Or, finally, leave the two opposing judgments in place and perform sensitivity tests at the end. Maybe it will turn out that the disputed judgment does not affect the outcome.

The resulting structured decision model – with priorities derived through the judgments of the group – represents the collective understanding of the issue quite clearly, even to those who did not participate in the process. If top management produces a strategic map of business objectives, with their priorities explicitly stated, lower level managers should be able to translate them into more specific sub-objectives, actions, and so on throughout the organization.

The development of electronic media has opened wide opportunities for enhancing group collaboration. Today somebody who joins the group in the middle of the process can easily catch up with the group’s thinking. And being able to represent the team’s thinking process is important because what we learn during the process often contributes more to our understanding than just learning the final conclusion.

Using the same medium for collective work moves the center of attention from individual team members to the problem itself. It minimizes the problem of disagreements that might be perceived as personal attacks. Since conversation often creates confusion, having a visual object (a model in the case of group decision making) can reduce the confusion. The model is an object that can be manipulated, arranged, polished, reorganized, and improved by the group. As collaboration finishes, the model becomes a group creation that can be shared and documented for later review. Because a model tells a story better than a detailed narrative, it conveys more information to top management, making it easier to gain their support or for the issue to be reviewed and revised as the need arises.

The AHP/ANP, with its supporting DecisionLens software or SuperDecisions software, facilitates the collaboration process all the way from structuring the decision problem to presenting its outcome. It is a systematic process that helps a group leader orchestrate the process of engaging people so they can contribute their ideas to produce the best results.

Effective group decision making addresses both task-oriented goals and relationship goals by managing the group process [23]. An effective method needs to address the following major issues:

The AHP/ANP, with its supporting software, is helpful to a group leader in many ways. First, the group should generally be excited about their new assignment. Everybody should be committed to making a contribution, and many may have some idea as to how to do it. Some may be knowledgeable about the problem but feel overwhelmed by it. Group passion can be both exciting and tiring, however, because in the early stages the group may have neither a clear common objective nor any structure in the discussion. The group needs to set clear objectives and milestones to measure progress. The leader needs to focus on the objectives but at the same time must be open to different viewpoints and try to involve everyone in the process – promoting a non-threatening environment that stimulates the free flow of ideas and minimizes conflict as the group is encouraged to look for common ground to resolve its differences.

The AHP/ANP makes group decision making intrinsically efficient for at least three reasons. First, it provides a framework for group collaboration and tools that systematize the group process. Second, it enables the group to break the task into a set of subtasks and distribute them to the appropriate members or subgroups. Each can then work almost independently – minimizing the manpower required and allowing various group techniques to be used such as brainstorming and morphological analysis while still keeping them integrated within the larger unifying model. And third, it provides feedback measures to help the group improve their judgments while allowing a certain degree of inconsistency. The group may also decide to do a quick and cursory evaluation to explore what the likely outcome will be or to streamline the number of judgments. Accepting a certain level of inconsistency will also save time. It is important to run a sensitivity analysis to ensure that the final priorities of the favorite alternatives are not too close.

Consider the following case. A team of consultants was asked to give advice on restructuring a company with a head office located in the state and operations throughout the state. Working with a team of counterparts from the organization, the consultants agreed that the general idea of establishing several branch offices would lead to more effective operations. They realized, however, that they had to clarify the main roles of these branch offices with respect to the head office before moving on to details of the company’s structure. The consultants and the counterparts identified two separate strategies for the role of the branch offices and agreed on the criteria for selecting the best one. After analyzing the options they seemed to agree on the trade-offs needed to make the selection. When it came to judging which strategy was the best, however, the consultants and the counterparts differed. Even more troublesome was the fact that the consultants’ opinion, although it had been reasoned objectively and independently, happened to align with the inclination of the company’s top management. This situation raised a potential conflict as the counterparts began to wonder whether the consultants were really giving an independent recommendation.

At this stage the consultants suggested using the AHP to arrive at a group outcome. First they structured the decision problem in a hierarchy with the goal at the top, criteria at the middle level, and the two alternatives at the bottom. The process of providing judgments was rather easy since there were no significant differences between the two parties with regard to the relative importance of the criteria and their relative preference of the alternatives with respect to each criterion. The counterparts, who represented the decision makers in the organization, were given more say in the judgments regarding the relative importance of the criteria. The consultants served as experts by evaluating the alternative strategies with respect to each and every criterion; the counterparts had the decisive say in judging the relative priority of the criteria. Despite the apparent bias in the deliberations, this exercise produced an outcome that was ultimately the same as the one the consultants had recommended.

One problem was that the method had been applied without adequately introducing the theory to the counterparts. They were not familiar with the method and were suspicious about how the judgments were synthesized to get the outcome and to what extent the outcome was valid. The consultants addressed their concern by inviting them to estimate the relative areas of different shapes. After their judgments were processed by the software and they could see a reasonable estimation of the actual areas, the counterparts gained confidence in the method and trusted its outcome regarding the best role for the branch offices. They now supported the consultants’ earlier conclusion.

Now that they had the decision model, the consultants could present the reasoning behind the choice and explain how they arrived at that outcome, which improved top management’s confidence in the decision. The process of structuring the model promoted common understanding between the consultants and their counterparts, validated top management’s inclination, and contributed to a more productive consultation overall.

The AHP’s systematic approach lets the group see where the problems lie so they can be addressed at different stages of the process using different techniques. Structuring the hierarchy captures the group’s understanding of different elements of the problem and hence the possible source of differences. Using the structure and the pairwise- comparison method to elicit judgments narrows the possible source of differences considerably. Clearly it is easier to reach consensus on comparing two things than on many things at once. The AHP makes it even easier to compare two things by not requiring a group to reach total consensus on a judgment. Instead, a combined judgment can be produced by taking the geometric mean of the individual judgments, though prudence suggests that discussion is needed when the judgments are widely disparate and that automatic use of the geometric mean should be avoided.

If there are relatively small differences, the leader may use one of the following techniques:

Larger differences may indicate that there are other sources of difference and the solution may be to expand the hierarchy. If the difference concerns matters of value, the group can use one of the following techniques:

Discussing the differences first and then appointing certain people to vote can help narrow the range of judgments. The majority is not always right.

The major role of a group leader in this context is to manage the intertwined goals of achieving content and having a smooth process. Although the leader is generally not expected to be an expert in the problem, this person must be an expert in keeping the goal in focus and managing the group process. The group is expected to fulfill its mission and, while doing so, strengthen the bond between team members. A group leader faces several challenges:

There are different kinds of decision problems – selection, prediction, and resource allocation, for example. Most decision-making methods are designed for a selection problem: choosing the best among a set of alternatives. But there are other kinds of decision problems – predicting what the future holds, for example. With regard to the measurement scale used to make the judgments, only methods such as the AHP/ANP that use cardinal measurement can produce meaningful outcomes. With the AHP/ANP, the process involves the following basic steps:

Prediction in a stable environment, viewed as “estimating future events,” has been approached using forecasting methods that extrapolate from past data using techniques such as regression analysis. Forecasting calls for subjective judgments from the group or experts with a method such as Delphi [25]. It has been shown that the AHP/ANP predicts future events better when they are viewed as the effect of actions taken by the different parties involved. It is a problem in a many-party environment. Hence the model must relate to the environment – comprised of people, their objectives, their policies, and outcomes – from which we derive the composite outcome (the state of the world).

In the previous section we saw how the AHP/ANP with its supporting software addresses group process goals such as enhancing leadership effectiveness, facilitating learning, allowing for prioritizing judgments of group members, and helping resolve conflict. But a reliable theory for group decision making must also satisfy certain content goals to ensure valid and useful outcomes, particularly when predicting [26].

The entire AHP/ANP model can be viewed as a description of the problem – which may be to find the best solution, to assess a situation, or to predict the likely outcome of current forces and influences. The AHP/ANP, at least in theory, poses no constraints on how broad and how deep to go with a structure. For effective decision making, though, the model should be neither too broad nor too detailed.

There are many creativity techniques that can be used to generate alternatives for the AHP/ANP model. The process of structuring the model and making the factors explicit, can trigger thinking about what the alternatives should be. Thus with the AHP/ANP the very process of defining and structuring the problem is integrated with designing a solution. After the process is completed, reflection may lead the group back to refining the problem’s definition. The AHP/ANP does not impose limits on how groups structure their thinking. A decision making method is essentially about eliciting tacit preferences from the decision makers. The AHP/ANP does not require physical measurements as inputs though such information can be used if it is available.

A multicriteria decision making method should make it possible to elicit judgments that faithfully represent the real world and give credible results when synthesized for the complete problem. The group should be able to incorporate differences in status and power among its members and draw on their special expertise to enhance the validity, accuracy, or implementability of the outcome. Having a synthesis rule that produces credible results also means that the mathematical aggregation of judgments must satisfy the rational condition of group aggregation. Finally, there needs to be a way to conduct sensitivity tests evaluating how changes in judgments might alter the results.

Ultimately the method should generate an outcome that is valid and generally useful for two fundamentally different types of decision – either simply taking the alternative with the highest number (as in the “select the best” kind of problem) or interpreting the numbers as a distribution used in resource allocation or predicting the likelihood of a different future scenario. Validity of the outcome is the bottom line requirement for group decision making. Since the AHP/ANP is a theory of priority measurement the outcome can be used in either type of decision. With the AHP/ANP knowledgeable people can build models, enter judgments, and produce outcomes that match those in the real world.

Consider a voting situation where three people A, B, and C select in a democratic way the best among three candidates X, Y, and Z. The votes enable the people to order the three candidates from the first choice to the third one. Let A, B, and C order the candidates as XYZ, YZX, and ZXY respectively. The winner is determined by the majority of votes. Two voters prefer X to Y, two voters prefer Y to Z, and two voters prefer Z to X. We are generally rational creatures, so if we prefer X to Y, and Y to Z, then we must prefer X to Z. Unfortunately, majority voting does not produce a rational outcome when relative preferences are expressed in ordinal terms [27]. This phenomenon mentioned in Chapter 1, and with a little more detail here, was formalized by Kenneth Arrow as Arrow’s Impossibility Theory which says that it is impossible to derive a rational group choice from individual ordinal preferences with more than two alternatives [28]. Given a group of individuals, a set of alternatives that includes A and B, and the individuals’ judgments of preference between A and B, Arrow's four conditions are as follows:

The generality of Arrow’s impossibility statements makes any method of ordinal aggregation problematic. Consequently, the outcome of such aggregation depends on the method. In other words: There are many ordinal aggregation methods to choose from, and different methods may give different outcomes. It has been shown that the AHP/ANP, using absolute scales, removes the impossibility once and for all.

James Surowiecki, author of The Wisdom of Crowds, observes: “While big groups are often good for solving certain kinds of problem, big groups can also be unmanageable and inefficient. Conversely, small groups have the virtue of being easy to run, but they risk having too little diversity of thought and too much consensus” [29]. We agree with him that “diversity and independence are important because the best collective decisions are the product of disagreement and contest, not consensus or compromise.”

We assume that the group is composed of people who are knowledgeable about the problem. Given a task, the different perspectives of the group need to be elicited and then represented in terms of consensus on a specific goal. The group leader needs to understand the method. The members need to understand at least the basics and trust its validity. Collaboration is a process of producing something tangible, so the group should know what to expect. Numerous AHP/ANP examples can be shown before the group starts its deliberations. If there is a model that addresses a similar problem, they may want to use it as a template. The group may also learn about the problem by examining similar examples. Being familiar with the whole process and accepting it creates a sense of harmony from the start and builds mental alignment.

Every decision requires having alternatives to choose from. A single alternative leaves no room for choice because then the decision is already made. Listing a comprehensive set of alternatives is therefore a critical step in making a good decision. Otherwise, making a decision is like gambling with the unknown. Implementing the scientific method to select the best choice when there are not enough choices will not be of much help. Indeed the best decision may not even be among those alternatives being evaluated.

Not only is devising a set of alternatives essential, but encouraging creativity at this stage makes a breakthrough decision more likely. Brainstorming enables a group to generate more alternatives than the traditional way. Brainstorming means that any judgment which may inhibit creativity must be deferred. Despite its wide use, the technique does have limitations and has been modified over the years. One of its modifications is brainwriting or ideawriting because the use of writing is considered to be better than presenting ideas orally as there is less danger of domination by certain participants. It also encourages people to participate who have trouble expressing their ideas orally. Participants have a chance to phrase their ideas clearly in writing beforehand or allowing them to be recorded. The method will not work, however, if people are unwilling to express their ideas in writing. It works best with small groups, so big groups need to be broken into smaller groups in parallel sessions. After a proper introduction is given and a stimulating question is asked, group members write their initial response on a given form. They then react in writing to each other’s forms. After each participant reads the comments, the small group discusses the principal ideas that emerge from the written interactions and summarizes the discussion in writing.

Other modifications of brainstorming include bug lists and negative brainstorming (generating complaints to identify weaknesses), the Crawford blue slip method (independently brainstorming in response to a number of questions that are related to a problem), and free discussion among group participants. Brainstorming has been used in complex problems to generate questions rather than solutions. The outcome is a list of questions that the group decides to pursue to move the process forward.

Decision making is the art of managing the iterative process of divergent and convergent thinking aimed at doing the right things right. Divergent thinking needs knowledge and creativity; convergent thinking needs organized thought with purpose and direction. This focused outcome may again be subject to the next divergent thinking process. Too much divergence breaks collaboration down, and too much convergence leads to narrow and short-term actions. Thus the group needs a strong leader and a structured method to balance the two.

Belbin [30, 31] argues that a group should have diversity in its team roles. Interestingly, his finding suggests that having more than one creative Plant in a group or having a Shaper as the group leader may actually reduce the group’s effectiveness. It is not always easy for an organization to establish a team whose members have both the relevant knowledge regarding the task at hand and complementary characteristics so they can take on the necessary team roles. The AHP reduces the need for such diversity. While most people have a strong tendency toward a certain role, many also have the flexibility to take on different roles. The AHP/ANP can be used to help people shift roles. The ideal person to apply the AHP may be the participative Coordinator, for example, as opposed to the more directive Shaper, since the AHP is usually applied when the group is not pressed to make an urgent decision. Even so, a Shaper may find that using the AHP can help him to be more of a Coordinator. He can use his directive strength to help the group succeed rather than driving it to a certain outcome. A Shaper is usually more content-oriented, so he can learn to clarify issues as the group structures the task at hand. The problem of having more than one Plant is reduced because having more alternatives is generally a good thing. Moreover, with the AHP/ANP the decision is derived from the collective judgments, not by following some strong individual directly to a certain conclusion. The systematic process of the AHP helps a person with flexibility to pick the proper role at the proper time.

A group may think that it needs an expert’s assistance to come to a better decision. Experts are outsiders who do not belong to the group, although they may come from within the organization. The advantage of using experts is that it improves the quality and reliability of the decision without burdening the group with too many specialists or having to worry about how they relate personally to a particular expert.

A group usually invites experts to evaluate alternatives or elements in the model that have already been identified by the group. These evaluations may include quantitative or qualitative judgments. For example, a multinational company may want to open a new branch in a foreign country and therefore establishes a group to recommend which country. The group may be able to make a short list of preferred countries together with a set of selection criteria and their relative importance, but they may not have enough information or experience to judge how well the alternatives meet the criteria. Or perhaps they have made some initial evaluations but are not so sure about them. In this case, they may want to invite experts to make the judgments for them or to validate their initial judgments. Although two experts in the same field may not necessarily have the same judgments about things in their domain of expertise, we can hope that their judgments will not differ by much.

The group may also seek help from experts to develop alternatives by constructing different objectives or suggesting courses of action. The group may ask the experts not only to establish alternatives but to evaluate them as well. The group itself must develop the criteria and judge their relative importance, however, because they represent what the organization values most.

Given a set of alternatives to be evaluated, the group may then face the problem of deciding whom to invite. They may already have a list of reliable people they have worked with in the past. If not, the group has to make the decision – a simple example of interdependence in group decision making. The experts they choose will depend on the problem they have, and the outcome of the problem will depend on the judgments of the experts. The group may select experts based on their experience, the quality of their past work, and suggestions from members or other people. The group must be aware, however, that even the most qualified expert may not know it all.

A general method for group decision making must give a facilitator the means to lead the group and achieve its goals. The method must enhance individual and group learning. It should enable the group to solve problems and make incremental improvements based on past performance and knowledge. It should also urge them to question their assumptions for a breakthrough in knowledge. Systematic development of alternatives means that the group must not view a problem too narrowly to ensure a meaningful solution or too broadly to ensure controllable actions. It also means that the group must be able to define a set of distinct alternatives with the proper degree of abstraction. A group of top executives, for example, would view a problem from a higher level of abstraction than a group of operational managers. Analysis of alternatives means that the group must have a model with the appropriate breadth (for relevance) and depth (for precision). Successful analysis depends on faithfulness of judgment elicitation, psychophysical applicability, and the depth of the analysis. In some methods, for example, you must first accept the premise that eliciting judgment by comparing two alternatives with respect to a certain property will produce the most faithful representation of your tacit preferences.

A faithful judgment can be obtained if:

Depth of analysis refers to how well an analytical method guides a decision maker’s thinking to ensure the validity of the outcome. It includes, for example, having a feedback mechanism for making adjustments or directing the decision maker to an outside expert. Fairness is addressed not only during group interaction but when information from different individuals must be mathematically aggregated into one judgment for the group. For this criterion, we are only concerned with the method of aggregation, since group discussion is likely to be controlled by the leader.

With regard to resource allocation, a decision theory must allow the group to separate the alternatives with cardinal numbers rather than simply order them. Indeed the members themselves may need to be weighted as to the reliability of their opinions. Other parties who may be affected by the decision often need to be considered, too, and a successful method must have a way to include their judgments.

Most significantly, we add, a method must be generally applicable, valid (capable of being scientifically validated), and reflect the truth advocated by those who provide the judgments. Thus we are concerned with issues like these: Is the method applicable in conflict resolution? Does it apply to intangibles in the same way it does to tangibles? Does it have mathematical validity and generality, and is it supported with axioms and theorems? Can the method be applied to psychophysical measurement? And is the outcome valid – ensuring, for example, reliability in prediction?

To be applicable to conflict resolution the method must provide a way for each party to evaluate the costs and the benefits of giving up something in return for getting something from the other party. Applicability to intangibles refers to measurement of the multidimensionality of the factors involved. Mathematical validity and generality call for a formal mathematical representation of the reasoning behind a theory and economy in the assumptions required for its generalization. Psychophysical applicability means that an analytical method must deal with the measurement of relationships between the physical attributes of stimuli and the resulting sensations reflecting diminishing response to increasing stimulus, such as, that described by the Weber-Fechner law. Validity of the outcome involves the accuracy of the outcome in predictions. We need to be careful, however, to define what constitutes a prediction situation. In an experimental study, Schoemaker and Waid [32] showed that guesswork with direct estimation of the rank of multicriteria objects produces a very different ordinal ranking than that of the cardinal ranking produced by another method. Following are some of the reasons the AHP /ANP are so effective.

Group maintenance: leadership effectiveness. Group leadership ranges from the autocratic to the democratic. We assume that the group works mostly with moderate situational control in terms of leader/member relations, task clarification, and status. The ideal method is one that not only encourages group collaboration but also provides the necessary control mechanism to guide the leader in pursuing the group's goals. It should also offer the means for structuring group knowledge and technical computations that do not involve much interaction or leadership. The highly systematic approach of the AHP/ANP means it satisfies this criterion.

Group maintenance: learning. We assume that objective knowledge is considered less important by the people involved in the group than what they know from their own experience. Learning ranges from acquiring objective knowledge, which has little to do with group members' subjective values, to improving their understanding of cause-effect relations in a problem and questioning the underlying assumptions behind certain decisions or actions. The AHP/ANP provides a compact description of the problem that facilitates learning beyond membership of the group. In an experimental study participants ranked the AHP as the least difficult and most trustworthy method among those studied. And the easier to apply and the more trustworthy a method is, the more we can learn from its application.

Problem abstraction: scope. The need to abstract a problem or define it is at the core of all decision making. Modeling is a common approach to this process. Simplification is inherent in modeling, however, as it is used to promote understanding. An ideal method would broaden the scope of problem abstraction without posing constraints on the complexity of group thinking. The AHP/ANP enhances problem abstraction, but it must be combined with other techniques to broaden it. Morphological analysis, for example, with its systematic search for combinations of attributes, may produce more alternatives and help to uncover the assumptions hindering implementation of the suggested solutions.

Problem abstraction: development of alternatives. Alternatives are not usually given to the group; hence problem structuring must go through a process of selecting alternatives. We assume that multicriteria methods allow a certain degree of interaction among group members. Problem abstraction may or may not lead to a set of alternatives. With the AHP/ANP, however, the level of problem abstraction provides the opportunity to question whether the alternatives are appropriate for that level of abstraction. Applying creativity techniques such as brainstorming can improve the quality of the alternatives for an AHP/ANP model. It has been reported, however, that brainstorming is the least effective technique. Morphological connection has been found to be mostly useful for new product or new system development. The nominal group technique (NGT) and the Delphi method can be used to align group members’ perceptions.

Structure: breadth. A structure is said to be broad if it has many distinct elements (criteria) that are assumed to be independent of each other. A problem that is modeled by more than one such structure is considered to be even broader. The AHP/ANP theory does not limit the number of criteria considered in the analysis. This is up to the decision makers. Although too broad a structure with too many elements increases inconsistency in judgments, the AHP/ANP provides a way to deal with this issue.

Structure: depth. A structure is said to be deep if each element is broken down into sub-elements, each sub-element into sub-sub-elements, and so on down to the most detailed elements. The AHP/ANP theory does not limit the level of detail with respect to breaking down criteria into subcriteria, sub-subcriteria, and so on.

Analysis: faithfulness of judgments. A judgment is said to be faithful if it is a valid and accurate representation of the decision maker’s sense of order. The AHP/ANP way of deriving priorities is a proven method for eliciting faithful judgments – as shown by the rigorous validation of its Fundamental Scale and its many applications in prediction that produce accurate results. Judgments can be expressed in a way that fits the decision maker best (numerically, verbally, or graphically). Objective measurements can also be used to represent judgments.

Analysis: breadth and depth of analysis. The structural flexibility of the AHP/ANP facilitates in-depth analysis of a problem. It also provides inconsistency and incompatibility measures to indicate whether some improvement in judgments is called for and whether some effort to align perceptions among group members is required. Its supporting software indicates the sources of inconsistency and incompatibility and offers a means to conduct a sensitivity analysis.

Fairness: cardinal separation of alternatives. Cardinal separation of alternatives refers to the aggregation of individual judgments. As we have seen, Arrow's theorem indicates that ordinal preference relations do not treat the alternatives fairly. The AHP/ANP use of an absolute scale, however, removes Arrow’s barrier.

Fairness: prioritizing of group members. With group decision making there may be times when the group wants to apply the concept of fairness to its members. For example, the group may wish to assign weights to the members according to the relevance of their expertise, their previous contributions to the goal, or their knowledge about certain criteria. With the AHP, it is up to the decision-maker to determine what concept of fairness is appropriate. A hierarchy can be structured with all the different members at the bottom. The criteria levels may include responsibilities or expertise that can then be used to prioritize the members.

Fairness: consideration of other parties and stakeholders. The AHP is the only well-known method that explicitly includes other parties’ concerns in detail as part of the problem structure and then quantifies them.

Scientific and mathematical generality. The mathematical foundation of the AHP with its axioms is generalized in a natural way to the ANP without additional assumptions.

Applicability to intangibles. The fundamental measurement of the AHP/ANP can be applied to intangibles in a natural way, and the user can decide whether to use relative, ideal, or absolute measurement.

Psychophysical applicability. Psychophysical applicability involves the issue of stimulus/response. The AHP/ANP addresses it without adding complexity to a model. It has been shown with many examples that its priority-scales approach has produced measurements of responses to physical stimuli that correspond closely to the normalized values of physical measurement.

Applicability to conflict resolution. A method must offer a way to find the best solution for a group conflict – a solution that is understandable, acceptable, practical, and flexible. The desire to be secretive makes it hard to use such a clear step-by-step approach, however, so people often resort to less structured and less explicit methods. The AHP/ANP makes it possible for them to work out their solutions separately, and then debate, weighting as necessary, to combine their final priorities into a final group outcome.

Validity of the outcome (prediction). We can evaluate the strength of the AHP/ANP and prove its validity. The AHP/ANP’s reliance on absolute scales that are derived from paired comparisons enables us to model a problem by ordering its elements and levels in a finely structured way to legitimize the significance of the comparisons. Sometimes, however, a method does not perform as intended. Instead of directing decision makers to profitable investment, for example, a series of experiments indicated that use of the Boston Consulting Group (BCG) matrix increases a person’s likelihood of selecting a less profitable investment due to misuse of the method. Several applications of the AHP/ANP to presidential elections, turn-around of the US economy, and to projected values of currencies versus the dollar, and even to the outcome of sports competition, indicate that the details included in the structure and the expertise used to provide the judgments produce surprisingly close numerical outcomes to what actually happened many months later.

Group decision making is essentially a process of turning many individual preferences into a decision by the group. Prior to the AHP, a theory for aggregating people’s cardinal preferences was considered unfeasible if not impossible. Arrow's barrier created a distinction between procedures for electoral or social choice and those of decision making in organizations. The former generally use formal approaches (normative, quantitative, axiomatic science) with well-formulated voting questions representing the decision problem and assuming no interpersonal interactions among people in the population. The latter rely on intensive interactions among individual members, depending on the complexity of the problem, and it is here that the term “group decision making” is usually used. Such a group can be considered a synergistic group; its task is to combine the knowledge of its members to come to a collective outcome. Involving practically no quantitative method, it is a synergistic approach that is made possible because the group members come from the same organization – implying the existence of common objectives that make them interdependent.

The AHP has removed Arrow’s barrier and hence makes it possible to link the two otherwise unconnected worlds of electoral choice and group decision making. The AHP has been used to integrate voting with discussion and thereby creates a hope that somehow a more synergistic approach can be applied in the formal political decision making that now only uses yes or no voting. Synergistic voting is a formal process that includes representation of common objectives that belong to the same community.

Although it may not be realistic to expect that such a voting process will be implemented in the near future, we can speculate on how the AHP makes it feasible. The AHP opens up a wide range of ways to vote, at least from the methodological point of view. Voting on a set of alternatives can be grouped into three key approaches:

It seems there will be more and more shifts in the way organizations are managed – from hierarchical structures with a static scope of responsibilities to dynamic team-based structures oriented toward project tasks. At the end of the continuum are collaborative organizations, where effective coordination is designed with shared decision making and then implementation. Collaborative processes are at the heart of this kind of organization: Multiple perspectives are used, synergies are promoted, and commitments are nurtured. Their concerns are how groups of people work and learn together as well as how different groups align themselves and learn from each other.

Implementing a collaboration culture breaks down the vertical and horizontal walls of the traditional organizational silos based on the assumptions that specialization works best and conflict is unproductive and hence needs to be prevented. Traditional organizations are divided into functional units such as marketing, production, and administrative support. Walls are built by having distinct job descriptions for each function that specify responsibilities and authority. Cross-functional coordination is achieved by observing a strict discipline that clarifies who does what to perform every business process.

A look at world-class organizations today will tell us that these assumptions are no longer valid. This is not to say that unique expertise is not important anymore; rather, the rigid boundaries of authority that come with each silo are getting blurrier. People’s expertise no longer corresponds exactly to what is required by their jobs. A world-class collaborative organization still focuses on business results – but without breaking jobs down into a set of independent functional responsibilities. Rather, the organization creates value by aligning different units to perform their specific roles. A conscious effort is made to build the employees’ sense of ownership and discipline. Flexibility is embedded in the organization’s policies, and procedures are put in place that emphasize personal accountability. Organization members learn from managing complex trade-offs and balancing their thinking between broadening their view of a problem and converging to a solution.

In one of the rare fully developed collaborative organizations, core groups of three to eighteen members emerged. They work across the boundaries of disciplines, plants, and countries. Decisions are made at all levels of the organization in a highly disciplined way based on a clear set of priorities and trade-off criteria. The AHP/ANP is an excellent means for deploying priorities down through the organization and communicating trade-offs clearly by providing guidelines for developing similar models for operational decisions and ensuring the alignment of efforts made by different parts of the organization.

Additional Reading:

Castellan, N.J. Jr. (ed.). Individual and Group Decision Making: Current Issues. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1993.

Micale, F. Meetings Made Easy: The Ultimate Fix-It Guide. Entrepreneur Press, 2004.

Pacanowsky, M. “Team Tools for Wicked Problems.” Organizational Dynamics 23(3) (1995): 36-52.